April 24- July 7, 2019

Who owns the power or controls it? Who has the power and can it be shifted, negotiated. Nature pitted against Humans is one of the most important power struggles of our time. Wealth against Poverty is another. People against Government. Religions against Each Other. Belief against Non-belief. Humans verses Religion. Past struggling with the Present as in language being lost to shifting history. Race against Race. Nature against Humans who are also part of nature—all timeless struggles. The North Dakota Museum of Art has acquired important works of art that reveal aspects of power and the conflicts over power. These will be in the exhibition along with contemporary work by four other artists timely today. The exhibition will span four decades, from1985 to the present. Rather than singular pieces the artists are represented by seminal bodies of work.

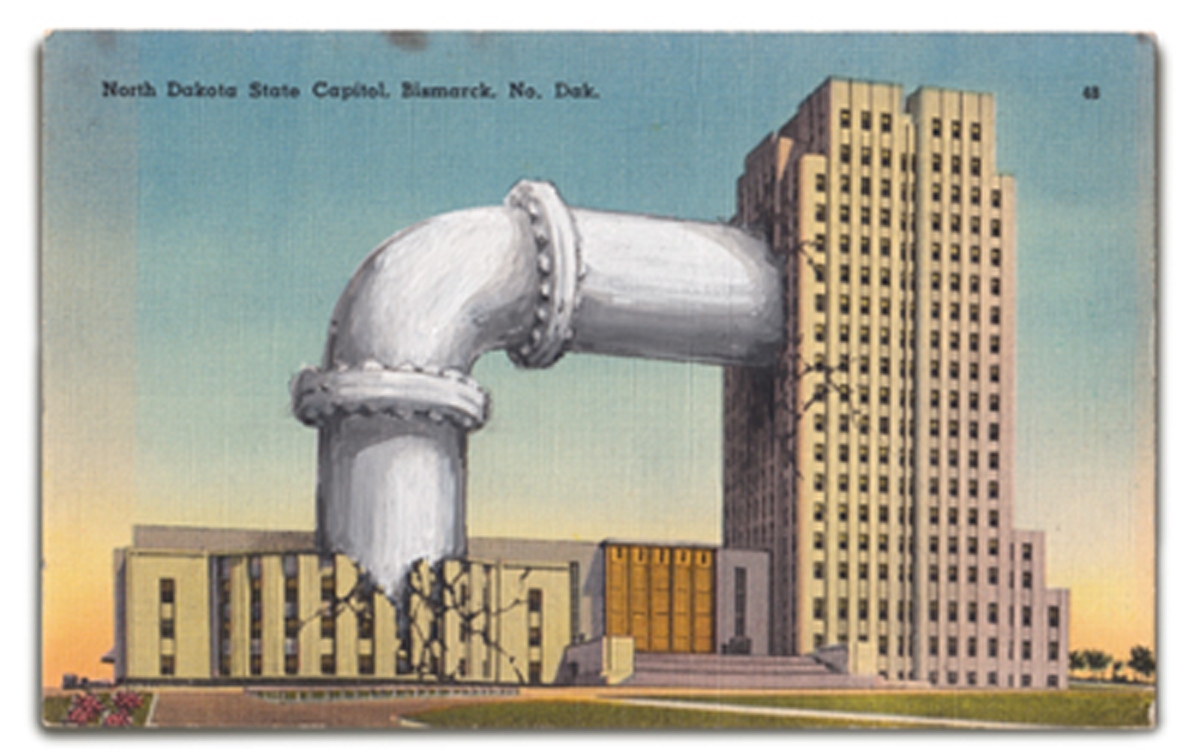

David Opdyke, Brooklyn, New York.

Public–Private Partnership, ND. Acrylic over-painte

on vintage postcard.

Collection of the North Dakota Museum of Art.

Gift from the artist.

David Opdyke. Brooklyn, New York.

This Land 2018-2019. 529 postcards

over-painted with acrylic.

Installation over 168 x 96 inches

With This Land, David Opdyke melds art and environmental activism, hoping to inspire urgent changes in vision, one postcard and viewer at a time. The installation looks like a mosaic of sorts. A grid-work array of colorful tiles (parts of which appear to be falling away toward the bottom), portrays a panoramic bird’s-eye view down both sides of a V-shaped valley, the sun rising in the pristine distance. A crisp, lush pastoral expanse.

A bit closer up, and the individual tiles reveal themselves to be vintage postcards from the first third of the twentieth century—black and white photographs overlain with stylized tinted colors, each one (and there are over 500) portraying a distinct slice of idealized Americana. Town squares, mountain highways, recently completed dams, main streets and county seats, lakes and rivers, forests and farmsteads: intimations of a prodigiously gifted country positively breasting its way into a confident future.

Michael James Boyd (1962 – 2005). Ojibwa from Minnesota. Untitled Mural, 2003. Acrylic on panel plywood, 8 x 24 feet.

Commissioned by the North Dakota Museum of Art

Michael Boyd was interested in not only the traditional but also contemporary scenes of everyday life. There is a little of everything from the city and reservation life for the Native Americans in his mural—drugs, fights, gangs, drinking, homelessness but also many positive things. The surface of the painting is smooth and fine, and the sun is bright and shining. While nature is a large presence in the mural, the energy of city life invigorates it with tension. Boyd believed, “Natives belong where they are comfortable, some are bored and miserable on the reservation, some are tired and worn out by the city.” He didn’t present the past as idealistic in his work. He painted the casino, reservation housing, and old cars, and balances it with the tranquil presence of nature.

The scene in the mural depicts familiar, everyday experiences. The life-size scale of the figures allows the viewer to imagine they are part of the painting, not only observing but also participating. The images are highly detailed and they glisten with precision.

Boyd was commissioned to paint the mural as part of “Meeting Ground,” a Museum festival. Composer Geoffrey Hudson’s composition was a collaboration between the North Dakota Museum of Art and the greater Grand Forks Symphony through the national Continental Harmony program. Hudson examines the interface between Native and western musical traditions, while the mural also examines the interface between the two cultures, giving the viewer fresh, new insight into Native culture at the turn of the twenty-first century.

Michael Boyd, was born in Cass Lake, Minnesota, the headquarters of the Leech Lake Ojibwe. He grew up in Squaw Lake, a small town of about 150 people, and graduated from Flandreau Indian Boarding School in South Dakota. His grandmother bought him a set of acrylic paints when he was fifteen and they both joined painting classes. He learned the basic concepts of painting and continued to paint throughout high school. He began focusing on Native American imagery, and developed these themes while attending the New Mexico Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He considered himself a self-taught painter who worked in construction for many years to support his art.

Rena Effendi, Dasan 10, Spirit Lake Reservation, 2013

Desan Cavanaugh, 10, has not cut his hair since he was born. Spirit Lake is a Sioux Indian reservation home to 6,200 people. Spirit Lake Reservation, North Dakota, 2014 World Press Photo Winner, Observed Portraits, 2nd prize singles

Rena Effendi, Still from Spirit Lake, 2013, 3 screen video, premiered at Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018.

Commissioned by North Dakota Museum of Art

Rena Effendi, born in Baku, Azerbaijan in 1977, grew up in the USSR, witnessing her country’s path to independence—one marred by war, political instability, and economic collapse. She took up the camera in 2001as a social documentary photographer. She documents complex social and political issues, which provide the world with human rights evidence, put faces onto a conflict, and documents the struggles and defiance of marginalized people.” (Open Society).

In August 2011, the North Dakota Museum of Art opened Effendi’s first solo exhibition in the United States, Pipe Dreams: A chronicle of lives along the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline that flows from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean. Her photographs captured the social and environmental impact of the oil industry on people’s lives—an impact echoed in the Bakken boom in western North Dakota.

In 2013, the Museum commissioned her to photograph North Dakota’s Spirit Lake Sioux Nation, to respond to reservation life today. Effendi directly faced this broken society, made friends, and told their stories through her photographs and video. Her haunting portraits explore the effects of trauma and the cycle of abuse in a place where poverty, chronic unemployment, addiction, depression, and suicide rates are startlingly high. She won the 2018 $20,000 Alexia Prize to continue her work at Spirit Lake.

Federico Solmi

Italy, resides in New York

The Amiable Despots, 2016

Acrylic paint, gold and silver leaf on Plexiglas, Led screen, video loop

34 x 52 inches

Federico Solmi, born in Italy in 1973, is a multi-disciplinary artist based in New York. Solmi’s work investigates the contradictions and inaccuracies of historical narratives that have led society to a chaotic era of misinformation in which the reality of media, celebrity, popular culture and consumerism in Western civilization establish an extreme and absurd world characterized by corruption and hypocrisy.

Solmi exploits emerging technologies to reveal the hypocrisies in contemporary society, making art with political and social commentary as a means to disrupt the power structure of our technological age. Using game engines, VR and artificial intelligence to create moving, painted worlds, the figures of Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and, of course, Donald Trump become the deluded puppets in Solmi’s video freakshow, showing us a version of the world expressed at the speed of the contemporary era. In Solmi virtual world our leaders become puppets, animated by computer scripts rather than strings.

John Snyder, Decorah, Iowa. The Communion, 2001 – 2003. Oil on canvas, 108 x 246 inches.

Collection of North Dakota Museum of Art

Gift from Martin Weinstein and an anonymous donor

John Snyder has always felt compelled to paint because “it’s the only medium that conveys the complexity of the images in my head.” He began The Communion as the second Iraq War was starting. Long interested in issues dealing with culture and religion, the artist reflected upon Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and other religions and belief systems during the two years he was painting this twenty-foot long mural. Snyder refers to historical events, such as the arrival of Europeans in the New World, juxtaposed with biblical events, such as the Annunciation and the Crucifixion.

He uses images of saints, martyrs, and mythic figures, as well as those of people or experiences from his own life. For example, he portrays his own niece as Mary Magdalene, smoking a cigarette while a halo glows about her head. Snyder includes figures, structures, and themes reminiscent of fourteenth-century Italian painting. He specifically echoes historical Italian painters such as Botticelli and Giotto while including portraits of twentieth-century luminaries such as Martin Luther King. The meeting of cultures and ideas that come together in this work, ripe with symbols and references to the past, challenge the viewers to construct his or her own historical perspective.

Snyder, originally from Marion, Iowa, received his BA from the Art Institute of Chicago. He next spent several years in Minneapolis working at the Walker Art Center. Currently he lives in Decorah, Iowa where he continues to paint, carve, and make woodblock prints. The Communion is one of three mural-sized paintings Snyder completed at that time. The Communion, The Judgment, and The Circus of the Night were placed in regional museum collections by his dealer Martin Weinstein and an anonymous donor.

Marcelo Brodsky

Buenos Aries, Argentina

The Undershirt / La Camiseta

Photograph from installation Good Memory, 1997

In 1976, a right-wing coup overthrew Isabel Perón as President of Argentina and a military junta was installed to replace her. During the ensuing Dirty War, some 30,000 people, primarily young opponents of the military regime, were “disappeared” or killed including the artist’s brother. The artist wrote,

This is the last picture of my brother Fernando, taken in the concentration camp of the School of Mechanics of the Navy (ESMA) before he was killed. Victor Basterra, a photographer who was also held captive and was forced to take pictures of the prisoners just before they were killed, recognized Fernando as he knew our family. He managed to smuggle the film out by hiding it in his clothes. This and other images by Basterra were used as evidence at the trial of the military juntas when the democratic process was restored on December 10, 1983.

Georgie Papageorge, Pretoria, South Africa. Suspension, 1989-90. Steel, mahogany, cow hide, acrylic on canvas, elephant bone, gold leaf, African woods, badger fur, 16.2 x 34.68 x 2 feet, weight over two tons.

Collection of the North Dakota Museum of Art, a gift from the artist

Suspension is based upon the concept of a suspension bridge that spans vast gaps—in this case sociological as well as physical. Suspension emerges out of great conflict and sacrifice. Based upon Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, both the physical and conceptual orientation of the work deals with the idea that through sacrifice, ultimate resurrection occurs. Physically the work is twin-sided, the front being symbolic of wealth, the back of poverty. Conceptually the whole work is seen as an extension of the human body, climaxing in the central transcendent ladder that is in itself a Tree of Life. The nest on top of the left vertical, which emulates an ancient North American Plains Indian Sun Dance pole, encourages the Thunderbird, or Bird of Peace, to rest in it.

Suspension was installed as the altarpiece for the Native American Thanksgiving Service at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, November 23, 1990. The service commemorated the centennial of the massacre at Wounded Knee, one of the darkest hours in the history of the United States.

Leonardo da Vinci painted his Last Supper between 1495 and 1498 in the Santa Maria Della Grazie in Milan, Italy. The broken construction lines reveal how Suspension’s whole structure evolved. Later, I realized that the horizontal lines of the table had become the base of Suspension.

—Georgie Papageorge

Artists include:

Paul Bowen, Wales, now residing in the US. Bowen’s Confessional sculpture probes the human relationship with God.

Michael Boyd, American Indian from Minnesota, depicts everyday Native life split between reservation and urban with his untitled mural.

Peter Dean, Jewish German, his family fled to New York in 1939. Dean painted the massacre at a New York gay bar in late 1970s.

Juan Manuel Echavarría, Colombian, Mouths of Ash video of six Pacific Coast Colombians who survived massacres, written songs that are sung on camera.

Rena Effendi, Baku, Azerbaijan, now living in Istanbul. Completed work under NDMOA’s on-going commission for her to record life today on the Spirit Lake Reservation. Photo and video screened last year at MOMA’s documentary festival. Two of the ten shorts were our commissions at the MOMA’s festival.

Daniel Heyman, US, drew portraits of innocent Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

Doug Kinsey, US, painted Albanian refugees who sought asylum in Italy but were turned away and not allowed to disembark boat.

David Krueger, US, animals in nature vs human hunters.

Lamar Peterson, US, Black artist painting the middle class Black America experience.

Will Maclean, Scottish, addresses the loss of Gaelic overrun by English.

Michael Manzavrakos, Greek American, prints on the power of the past to influence the present.

David Opdyke, US, Environmental installation, This Land. Full page article about this installation featured in the New York Times by Lawrence Weschler.

Georgie Papageorge, South Africa, Altarpiece created for Thanksgiving American Indian Service at Cathedral of St. John the Devine.

John Snyder, US, Religions vs religions.

Federico Solmi, Italian New Yorker, three works about Europeans meeting Native people, digital video with painted frames.

Richard Tsong-Taatarii, Part American Indian, photographer for Minneapolis Star Tribune who covered the Standing Rock Protests.